Woven Fabrics

We make woven fabrics on a loom. The weaver strings the lengthwise threads first, and we call them the “warp”. Then threads are woven through them creating the fabric. We call these horizontal threads the “weft” or the “woof”. We’ve named the edges of the fabric the “selvages” or “selvedges”, and we weave them more tightly to prevent fraying.

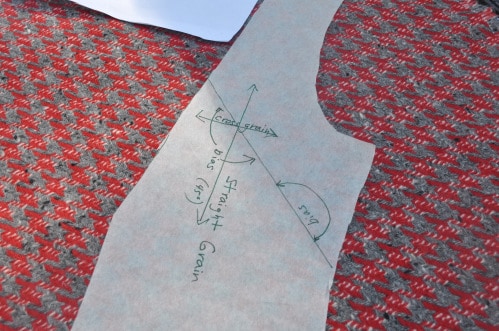

The warp creates the “straight grain” of the fabric, and the weft creates the “cross grain”.

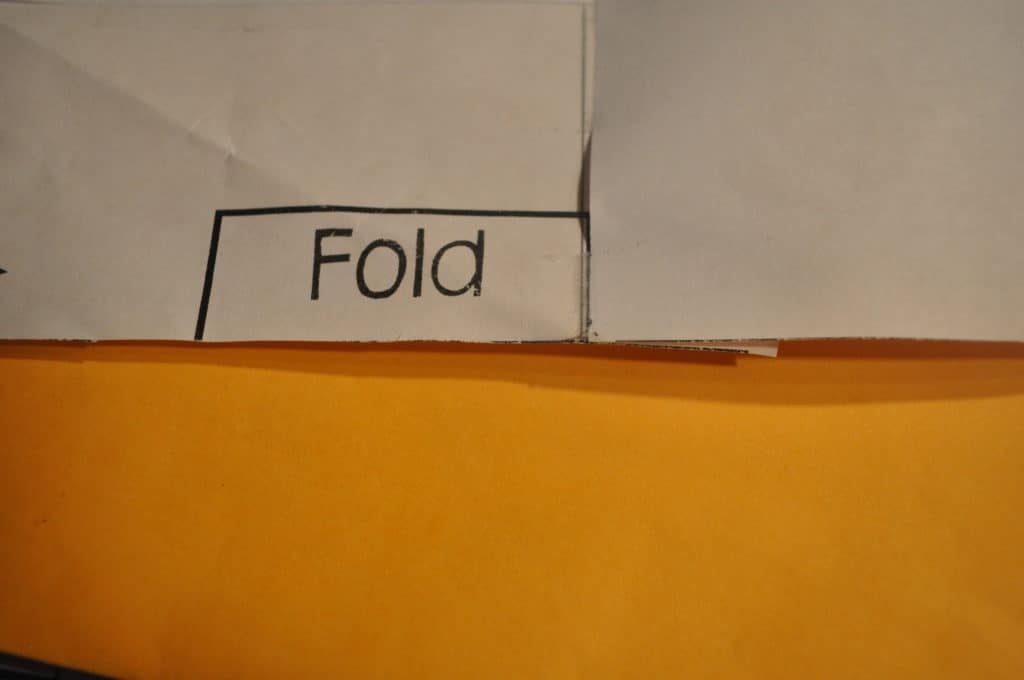

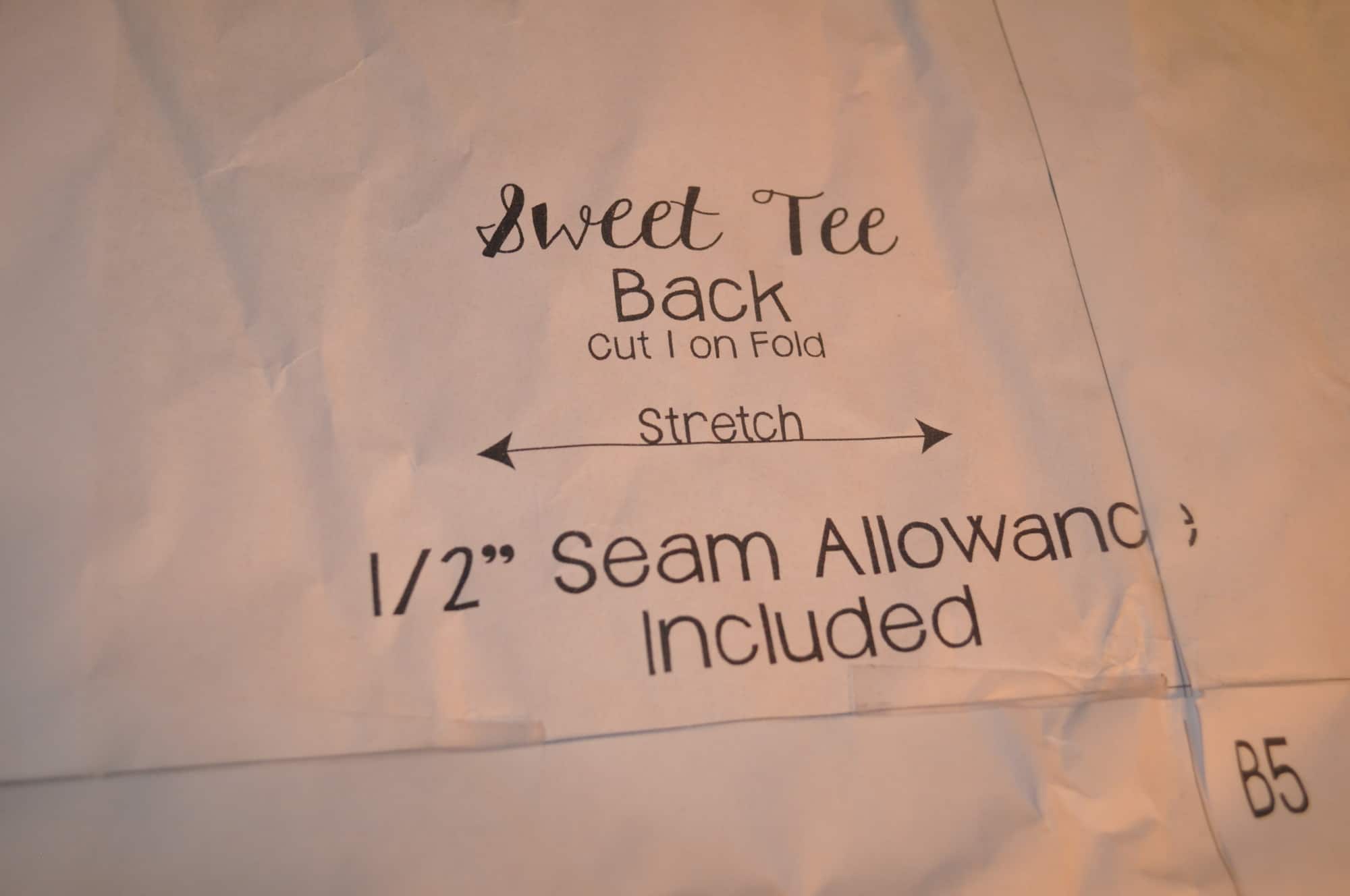

Pattern pieces have grainlines printed on them. They are either arrows or fold lines.

When we cut a pattern out, the best way is to fold the fabric carefully on the straight grain of the fabric, lining up the selvages . If you need to straighten the ends of your fabric, take a snip through the selvage near one end. Then pull a horizontal thread. The missing thread will create a straight line for you to cut along.

Then place the pattern pieces down carefully with the grain lines on the pattern piece lined up with the straight grain of the fabric.

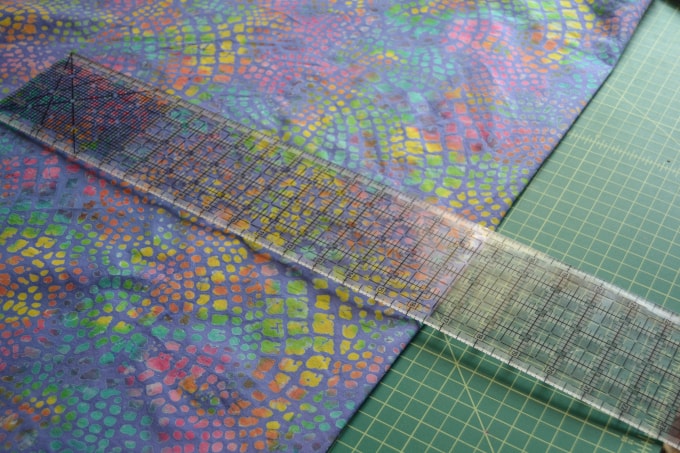

An easy way to check if your pattern piece is “on-grain” is to measure from the line on the pattern piece to the selvages in a couple of places. The distance should be the same.

It’s important for long pattern pieces, especially something like a pant leg, to be grain perfect. If it’s not, the garment will twist, and once you cut it, there’s nothing you can do to fix it. You’ll also never be able to match stripes or plaids if you cut off-grain.

Smaller pieces like pockets, collars, cuffs, and yokes can be cut on the straight grain, the cross grain, or the bias no matter what the lines on the pattern say. The “bias” is the direction that’s 45 degrees from the straight grain. It has more drape than either the straight grain or the cross, and edges cut on the bias don’t fray.

When you cut major pieces on the bias, it’s important to cut them in opposite directions or your whole garment will twist. But it’s not important for small pieces like pockets.

You can mark the bias on your pattern piece with a protractor or a quilting ruler.

Over time fabrics cut on the cross grain will droop more than then fabric cut on the straight. It’s not a problem for something like a skirt or pants made from a border print. The droop won’t be noticeable in the normal lifetime of the garment. You might see it in heavy curtains, though.

Knit Fabrics

Technically, knit fabrics don’t have a grain, but the direction you cut your pieces out matters just as much. Big machines make knit fabric, but they work the same way we knit with yarn and needles. Some machines knit back and forth and some knit in the round. One results in a fabric with selvage-like edges and other in a tube of fabric.

No matter what yarn is used to create the knit fabric, the single knit process will result in a horizontal stretch in the fabric we call the “mechanical stretch”. Fabrics that only have horizontal stretch are usually called “two-way stretch”. The addition of elastane (Spandex, Lycra, etc.) to the yarns can create a fabric with both horizontal and vertical stretch, and it is usually described as “four-way stretch”. Whether the fabric is two-way or four-way, the horizontal stretch should be the circumference of your garment.

While the amount of elastane in the yarns might make the fabric stretchy enough for the garment to fit you cut with the vertical stretch used as the circumference, you shouldn’t cut it that way. If the mechanical stretch in the fabric hangs vertically, you’ll get elephant knees, saggy elbows, and baggy crotches. You can use the same method for making sure your pattern is lined up so the grainlines on your pattern are parallel to the edges of your fabric that we use for wovens. Knit patterns often have the horizontal stretch line marked, too.

There’s a saying in sewing- The fabric always wins. There is probably nowhere in sewing where fighting the fabric is more futile than not paying attention to the grain.

Roberta